|

Jerry Hadley

A Sweetness |

|

| ||

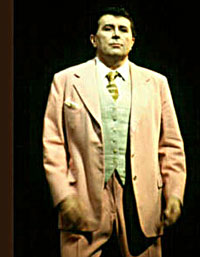

We're neither pure nor wise nor good; The first refrain soars; the final line subsides with resignation. It is a metaphor. The voice that sings these words from Leonard Bernstein's Candide has a pure, ineffably sweet, achingly sad beauty to it. It belongs to the late tenor Jerry Hadley, chosen by Bernstein himself as his ideal hero. As one listens, one understands Hadley's affinity for Voltaire's hapless optimist. To Jerry Hadley, the artist and the man, creating optimism and joy in his art and in his relationships was a mission -- one in which he usually succeeded in grand measure. "Jerry sang from the bottom of his heart with soul energy," remembers mezzo-soprano, Frederica von Stade. If Jerry Hadley ultimately failed as an optimist, it was tragically himself that he shorted. Though his more than twenty-five-year glorious international career was ended by his suicide in 2007, the legacy of his quarter century in the limelight still burns brightly, the memories of his friendship, his caring, his kindness as a colleague and a friend remain undimmed. Jerry Hadley - one of the greatest American singers, a tenor of international caliber with a unique and unforgettable sound, a commanding stage presence, and the great gift of versatility -- built a career that took him far from his rural prairie roots. He was born in Manlius, Illinois, on June 16, 1952, of English and Italian parents. He grew up on a farm, far away from the sophisticated international capitals where he would play out his adult life. To those who knew him he sometimes confided stories about the difficult, painful relationship with his mother, though he told others of his deep and abiding love for his father, whom he paid tribute to in the last work he recorded, Daniel Steven Crafts' song cycle setting of Carl Sandburg's poems, The Song and the Slogan. He attended Bradley University in Peoria, studying voice and conducting and went on to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign where he earned a master's degree in voice and got his first performing experience in campus productions. He married pianist Cheryll Drake and moved to Connecticut where he was teaching music and studying with Thomas LoMonaco when he was discovered by artist manager Ken Benson and his then-partner, Eddie Lew. Benson tells the story which remains, he says, to this day one of his most

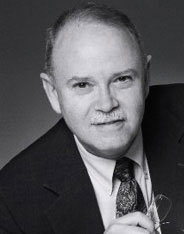

Benson and Lew represented Hadley until 1986 when Benson went to Columbia Artists Management to head his own division there. Initially, Hadley opted to stay with Lew because, as he told Benson, "I love you both, but Eddie as an independent manager, needs me more." Benson, who respected Hadley for his honesty and sensitivity, remembers a few years later receiving a call from Hadley who was seeking a new agent now that Lew was phasing out his clients. Hadley went over the names of possible new agents, seeking Benson's opinion. "I was kind of waiting for him to ask me, and he didn't. I hung up and then I called him back and asked, 'What about me?' He replied, 'Thank God. I was hoping you'd say that!' I often wonder what would have happened if I hadn't made that call," Benson chuckles. And so their collaboration lasted until a few years before Hadley's death when the tenor made the decision to take his career in other directions, but their friendship endured. "It was a long, good friendship," Benson recalls. "He was never difficult; we were almost always on the same page. He didn't require a ton of time and attention. He was secure in what he was doing, and if things were set up in the right way, he would do his part." Hadley was a trouper from the first. Benson tells of Hadley's early apprenticeship at the Lake George Opera, where, as customary, the tenor sang the title role of Faust in the afternoon and then performed in the chorus of the Mikado in the evening. Likewise, even after he received his break at the Washington, D.C. Opera which led to being engaged at the Vienna State Opera, Hadley insisted on honoring every one of the regional contracts he had previously signed. Hadley impressed Beverly Sills at the National Opera Institute auditions, and she offered him a contract for the New York City Opera, where he made his debut as Arturo in Lucia di Lammermoor in 1979 on short notice. The story of that evening is one opera fans still recount. As Benson tells it, Hadley, who had not had any stage rehearsal, tripped down the stairs, managed to get his sword stuck, then backed into one of the tall candelabras igniting the plume on his hat. "Never underestimate what can go wrong on stage," Benson laughs. "What seemed like a safe five minute debut turned into a comedy of errors. He learned from it, though." Sills, who had a marvelous sense of humor, could barely contain herself in her box. But it did not deter her enthusiasm for the young tenor whom she would showcase in leading roles for more than a decade. Hadley sang so many acclaimed successes for the now-defunct company, among them Les Pêcheurs de Perles, The Rake's Progress, Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny, and Werther.

Benson remembers the break in the early 80s that catapulted the tenor from "Omaha to Vienna." "Jerry had auditioned for Frank Rizzo in Washington, but it hadn't gone all that well. Then a tenor cancelled the entire run of Barbiere di Siviglia at the last minute, and Rizzo was desperate. He called several people who recommended Jerry. Rizzo hired him on a Sunday; Jerry threw his laundry into a bag and got on a plane. He was in the air when Rizzo made the connection that this was the kid who kept cracking at his audition. But Jerry proved him wrong, and he made a beautiful debut there. Rizzo became a great supporter." While he was in Washington, Hadley had the opportunity to perform at the Kennedy Center in La Bohème for the Reagan inauguration under conductor Lorin Maazel. "Maazel was just about to take over the Vienna State Opera," and Benson continues, "he offered Jerry five roles there right on the spot. Suddenly, we were negotiating contracts for him for Munich, Glynbourne, Florence, Covent Garden." Though he had been engaged to debut as Alfred in Fledermaus later in the year, Hadley actually made his Metropolitan Opera debut as Des Grieux in Massenet's Manon on March 7, 1987, after the original tenor and his replacement both bowed out because of illness. This time the stars lined up more fortuitously for Hadley, who was hailed for "singing sweetly with a healthy, hearty, light tenor." (NYT). Benson remembers being called to engage Hadley on a Thursday for a Saturday performance. "It was enough time for him to have his friends be there to support him. After his success, the Met rewrote his contract in much stronger, more favorable terms." At the Met, where he reigned for the next fifteen years, Hadley made distinguished appearances in Eugene Onegin, Rigoletto, Così Fan Tutte, Don Giovanni, La Traviata, Die Zauberflöte, Lucia di Lammermoor, Elisir d'Amore, as well as in modern works like The Rake's Progress, Susannah, and the world premiere of The Great Gatsby. The revival of Harbison's Gatsby saw Hadley's last performance at the Met in May 2002. For the remaining five years of his life he would experiment with taking his career in other directions, while still remaining active in concert, commissioning new works, teaching, and recording. Ken Benson explains the change. "There was a period in his early fifties when we realized the career was changing after twenty years, that it was time to step away from the Nemorinos. We began exploring some different kinds of repertoire -- some Britten, Janacek, Idomeneo, even Mime and character roles. He wanted to branch out and do some more popular things as well. I think he had a plan, and his main intent was to do good work." But sadly, there were complications. In 2002 he was divorced from his wife. The split left him reeling emotionally and financially, and according to Frederica von Stade, he confided that he was devastated over the estrangement from his two sons, Nathan and Ryan, whom he adored. "A wounded bird cannot sing. It was tough. It was emotionally distressing, and it goes straight to the throat. So I took some time off and sat in the quiet for a while," he told a journalist. "I never really understood how inseparable was the journey of the spirit and the journey of singing and making music. For the first time in my life, I couldn't see a way forward. But I came out on the other side of it with a deeper appreciation of what a great gift and great opportunities God has given me." Hadley spoke these words to the Australia Mail Courant in May 2007 on the occasion of his return to the stage as Pinkerton in Madama Butterfly in Brisbane, performances where the tenor was hailed for "a new-found sense of youth and clarity, coupled with a perfect technique and sure dramatic sense." Less than two months later he was dead, a week after shooting himself in the head with an air rifle in his Clinton Corners, NY home on July 10, 2007. That unspeakable tragedy silenced forever a voice that had been one of the treasures of opera history, but it could not extinguish the memory of Jerry Hadley's exquisite artistry. "There was nothing anonymous about his voice," Ken Benson asserts. "It was a full lyric tenor, slightly darker than usual, sensual, very accessible. He had a beautiful, distinctive sound that did darken over the years. And he was so communicative with words!" That voice was complemented by Hadley's histrionic abilities. He threw himself ardently into the grand dramatic passions of the roles tenors play, and he possessed an equal capacity for subtle and wicked wit. "Jerry was an excellent actor because he was all very much of a piece," Benson says. "[His performances] were organic; he gave the audience real, believable human characters and he was very involved facially and with the expressive potential of the words." "He was so wonderful to perform with," von Stade recalls,

But Hadley was a risk taker as well, especially with his repertoire. Over the course of his career he sang the gamut from bel canto to modern works, verismo to operetta, oratorio to Broadway shows, art song to pop song. And, amazingly, he succeeded at them all with stylistic aplomb. A three-time Grammy winner, he is one of the most widely and well recorded artists in recent memory. Among so many outstanding roles, his Nemorino in Elisir d'Amore is one for the ages- liquid sweetness and squillo in the voice and just the right blend of bumpkin and boyish hero; so, too, his Werther -- he was a master of the French style though it is difficult to listen to the last act these days without being overwhelmed by sadness. So, too, was he attuned to German operetta: he was a cheeky, romantic Alfred in Fledermaus, and a project he always cherished but never came to fruition was a production of what Benson calls "his own, very singable translation of Léhar's The Land of Smiles." And in Weill's Mahagonny and Stavinsky's Rake's Progress, as well as Harbison's Gatsby, Jerry Hadley was able to bring a raw dramatic and textual intensity that was riveting. But one of the things that Jerry Hadley did so extraordinarily well was the Broadway musical repertoire.

In the 1990s Hadley together with friend and colleague Thomas Hampson recorded and performed a program of tenor-baritone duets, affectionately dubbed "The Tom and Jerry Show." The first act consisted of classic operatic exchanges and the second Broadway duets, and the performances proved object lessons in idiomatic mastery of the respective genres. Benson reminisces about "the organic pairing" of his two clients, as well as "the long tradition for such partnerships, among them Bjoerling and Warren or Merill and Tucker." But it is on his recording of Broadway classics, Standing Room Only, that Hadley's haunting way with American show music leaves an indelible impression. He sings the full range from romantic to upbeat, plaintive to whimsical. To listen now to What I Did for Love is to understand the meaning of heartbreak or there is Les Misérables. "I remember his memorial service at University of Illinois," von Stade recounts. "It began in the dark and you heard the recording of Jerry's singing Bring Him Home --" she does not finish. Queried as to why Hadley succeeded so well in this music and in other mixed genres such as Bernstein's Mass and Paul McCartney's Liverpool Oratorio, Benson opines, " He met the music on its own terms. He sang it, but not in an overly operatic manner. It was his way of handling the English language, too; he never over pronounced." Von Stade agrees, adding," I grew up with Jerome Kern and Gershwin, and so did Jerry. There was a cherishing of the words and trying to keep simple some very difficult vocal things." That quest for simplicity and that focus on words also made Jerry Hadley a fine interpreter of song -- the classic European repertoire, of course -- but especially American song. Between 1995 and 1997 when I was attached to a PBS Great Performances project, Thomas Hampson: I Hear America Singing, I had the opportunity to work with Jerry on this repertoire. The surviving video showcases his energy, his charm, his versatility: he sang in a medley of folk tunes, Charles Wakefield Cadman's neo-Native American By the Deep Blue Waters, Charles Ives' boisterously characterized The Circus, and John Duke's Richard Corey. It is this last setting of Edwin Arlington Robinson's tragic poem about a man who "glittered when he walked" and who "one fine day went home and put a bullet through his head" that now unbearably unnerves, listening to it in Hadley's darkly manic performance. Hadley retained his interest in American song until the end. Two of his final collaborations were with composer Daniel Steven Crafts.

Hadley invited Crafts to submit some music and was pleased with what he heard. He told the composer, "I really love the way you set text. A lot of composers say they write melody, but you really do. I want you to compose for me." And so they selected Carl Sandburg poems for Crafts' cycle, Emmy-award winning The Song and the Slogan. It was premiered in 2000 at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign and filmed and recorded by PBS in 2004 in a performance that included Hadley's old mentor pianist Eric Dalheim and friend Barbara Hedlund on cello. The encore for the work was a song which Crafts had not been able to incorporate into the cycle, but which Hadley asked him to set separately. The Illinois Farmer is a beautiful, elegiac piece about which Hadley later confided to the composer that "for him the poem was about his father. I always get a little weak in the knees," he told Crafts "when I sing that poem which you set so beautifully." Ironically or perhaps fittingly, it was the last work Hadley would ever record -- the farm boy himself returning to his roots. Following the success of the Sandburg cycle, Crafts had also composed From a Distant Mesa for Hadley, who had fallen in love with the New Mexico landscape while he was performing in Santa Fe. The work for orchestra and tenor was on schedule to be performed at the New Mexico Symphony in 2008, when Hadley took his life. A concert version was eventually mounted with Hadley's protégé, tenor Brian Cheney, but Crafts says a full staging has yet to materialize. This passion for American opera and song remains a defining feature of Jerry Hadley's career. In many ways he was, as soprano Cheryl Studer called him, "THE American tenor of his generation." "Every young American tenor knows who Jerry Hadley was," Benson, who consults on voice and vocal careers at Juilliard, affirms. "Whenever I mention Jerry, tenors will light up and know his recordings. And that makes me very happy to know he is remembered." Frederica von Stade continues this train of thought: "When you spend your life singing in other people's languages and you are able to come home to American music, it feels SO good. We were somewhat lucky to be singing at a period when American artists and American music were experiencing a renascence." It is no coincidence that the present generation of tenors remember Hadley as one of their great forebears because he always took an interest in teaching and in supporting young colleagues. Indeed, one of the last profound relationships of his life was with his protégé, tenor Brian Cheney. Cheney, who still speaks emotionally about his mentor, says "I am trying to honor him through my singing. He was my mentor and best friend." Hadley, who had himself been mentored by the likes of Richard Bonynge and Leonard Bernstein, believed he had an obligation to "pay forward" the gifts he had received. Cheney tells how he met Hadley in 2004 when they were rehearsing and performing a new piece, Raoul, about WWII hero Raoul Wallenburg. "He was a big name, and we were all young singers. He was always jovial, but most of the others were afraid to approach him." Cheney recounts how one day he took the plunge and invited Hadley, who was by himself, to join the group for lunch. "We instantly hit it off, and after a week of rehearsal, he and I went out to dinner. He talked about his relationship with Bonynge and Lenny and of the responsibility for older artists to nurture young talent. He told me that he had promised Bernstein that if he ever got to the point where he could do that, he would. 'I think you are that person,'" Hadley told Cheney. "He never charged me a dime," Cheney adds gratefully. Thereafter, whenever Hadley was back in the area, he called the Connecticut-based Cheney, and they would work together.

But even more than this teacher-student relationship, the pair became fast friends. "He was breaking down so many walls for me," Cheney says. "We became very close and shared so much more than music. I realized after he died how open he had been with me." Cheney says Hadley regarded him as "a spiritual son," and they shared so many zany as well as serious times together. He narrates a story about accompanying Hadley to a meeting of history buffs who celebrated the Alamo -- how Hadley insisted they come costumed and how absurdly and riotously funny the experience had been. Cheney tells also of how, upon learning of Hadley's shooting himself while he was singing in Tulsa, he made a trip to the Alamo itself to mourn and remember. "He changed my life, so every time I would sing afterwards, it was hard," Cheney recalls. At the same time, it was a kind of therapy for me. One of my goals is to further his legacy, to keep his memory alive." Jerry Hadley seems to have universally inspired that kind of devotion in his friends and colleagues. "I found him to be generous, caring, and one of the most interesting human beings I have ever met," declares Crafts. "You felt safe around Jerry. He was glad to see you; he was always a comfort to me," von Stade reminisces. Benson concurs, stressing Hadley's integrity as a performer and a person. "He was a classic colleague. Everyone loved him. It was important to Jerry to be liked, and he was well liked. He was good at bringing people together, of diffusing tension with a joke, or making connections among people." His New York City Opera fellow tenor, Richard Leech concurs: "He was always there for his fellow singers, one hundred percent, and in an era of competition and vain rivalry, [Jerry] chose the other road, making those of us in his "club" of tenors feel like brothers." The Jerry Hadley I knew whenever I had the pleasure and privilege of working with him on a project was unfailingly kind, courteous, gallant, sensitive to the dynamics of situations and eager to promote harmony. Moreover, he had the gift of making everyone -- even those of us in supporting jobs -- feel important and special. This he did more often than not with his bright smile and infectious sense of humor. Hadley's jokes were legendary! "He was usually the life of the party," Benson remembers. "He loved telling jokes; he collected them. He would embellish them and play all the roles. Each time you heard the story, it was a little more elaborate than the last."

And he could use that sense of humor to take the edge off stressful situations. One of Frederica von Stade's favorite stories about Hadley tells of a performance she, the tenor, and bass Samuel Ramey were doing of The Damnation of Faust at La Scala. "It was one of those productions with everyone in black leather, and I think the idea was a romance between Faust and the devil, so they rolled around on the ground at one point, " she sighs in amusement. After that bit, "Jerry came off stage and said to Sam, 'I don't know about you, Sam, but I could use a cigarette.' He could just nail it like that every time!" Brian Cheney sums up the sunny side of Jerry Hadley with this caveat: "He was truly open, sweet, funny, but there were definitely moments when his insecurities would take over. Cheney talks of the darker side of Jerry Hadley's psyche, the side he kept, for the most part, so carefully hidden. In those last years, Cheney says he knew Hadley was depressed. "He understood that he wasn't singing his best. It wasn't that his technique had failed him; it was just that because of events in his life, he was singing scared." And Cheney also cites the business "which turned its back on him. Jerry took it so personally when he reached out to some people who didn't reciprocate." But like the other friends willing to talk about it, Cheney was still blindsided by the tragedy. "I was shocked, but I wasn't surprised. When he got back from Australia, I could tell something was wrong. My wife and I tried to talk with him, but he had a psychiatrist and he was on medication, and I thought he would be OK." Crafts agrees. "He was plainly down, but I had no idea his condition was so severe. He had met a woman he clearly loved, and things seemed to be looking up in general. He was looking forward to singing From a Distant Mesa. I miss him more than I can say." "I had so much of a sense that Jerry loved being alive," von Stade says quietly. "It is such a heartbreak that something knocked that will out of him." Like everyone else who expresses their sadness, von Stade, Crafts, and Cheney allude to the general feeling of helplessness and incomprehension that remains. But painful as they are, it is not these thoughts which prevail. "It is the voice that lingers in my mind," soprano Cheryl Studer states. There was the glorious tenor voice he gave his audiences as a professional singer. But then, there was his own very personal, warm, cheery, and very witty voice carrying through the halls to welcome his colleagues."

The voice - it is the voice we remember - the voice of an artist and a man - a voice imbued with great humanity, with large capacity for expressing both sorrow and joy. To understand this, we need only turn to another solo from Candide, the Act One meditation and listen to the tenor sing, "There is a sweetness in every woe; It must be so; it must be so." In these arcing phrases so filled with light and pain, we hear the sweetness of Jerry Hadley. It is in the voice, itself, that instrument of exquisite and exceptional loveliness; it is in the man who never stopped striving to love and be loved, and it is, most assuredly, in the artist's legacy -- in the ephemeral beauty of that song. Ephemeral, yet LASTING. It must be so. Carla Maria Verdino-Süllwold's reviews, interviews, and features on theatre, opera, classical music, and the visual arts have appeared in numerous international publications. She is also a Senior Writer for Scene4. Read her Blog. ©2014 Carla Maria Verdino-Süllwold

| ||

vivid memories of the tenor whose career he went on to manage for more than two decades. "It was 1978. Eddie and I were representing a baritone who told us he had this tenor friend who was teaching music whom he would like us to hear. We thought, 'A music teacher?' But we agreed to listen to him as a courtesy. Jerry rented a studio at the Ansonia Hotel where he sang for us. He was suffering from allergies and having problems with phlegm, and he was very frustrated because he thought he was doing a terrible job. But instead, Eddie and I were hearing this beauty of voice and these amazing communicative skills. We went out to a bagel place, and we sat Jerry down and told him we thought he was very special and we would be happy to represent him. He was thrilled!"

vivid memories of the tenor whose career he went on to manage for more than two decades. "It was 1978. Eddie and I were representing a baritone who told us he had this tenor friend who was teaching music whom he would like us to hear. We thought, 'A music teacher?' But we agreed to listen to him as a courtesy. Jerry rented a studio at the Ansonia Hotel where he sang for us. He was suffering from allergies and having problems with phlegm, and he was very frustrated because he thought he was doing a terrible job. But instead, Eddie and I were hearing this beauty of voice and these amazing communicative skills. We went out to a bagel place, and we sat Jerry down and told him we thought he was very special and we would be happy to represent him. He was thrilled!"

"because you would look at that face, and you were in it because he was in it. Everything he did was so genuine."

"because you would look at that face, and you were in it because he was in it. Everything he did was so genuine."

While many artists made forays into "crossover" music Hadley, along with Frederica von Stade and several others of their generation, redefined the term. His recording of Jerome Kern's Showboat with von Stade and Teresa Stratas, as well as his performances of My Fair Lady, Sweeney Todd, all evidence Hadley skill in this repertoire. Leonard Bernstein, when he recorded his final "authorized" version of Candide, chose Hadley to sing the title part, calling him his ideal interpreter, and surely, the surviving video and Grammy-winning recording bear out Bernstein's praise.

While many artists made forays into "crossover" music Hadley, along with Frederica von Stade and several others of their generation, redefined the term. His recording of Jerome Kern's Showboat with von Stade and Teresa Stratas, as well as his performances of My Fair Lady, Sweeney Todd, all evidence Hadley skill in this repertoire. Leonard Bernstein, when he recorded his final "authorized" version of Candide, chose Hadley to sing the title part, calling him his ideal interpreter, and surely, the surviving video and Grammy-winning recording bear out Bernstein's praise.

Benson remembers "Jerry always had a song project or a commission in the works." Crafts tells of meeting Hadley in San Francisco and finding their views of contemporary music copacetic. "We agreed on what it should be and perhaps more importantly what it should NOT be," Crafts says. "Jerry had no use for the perpetually dissonant styles -- he used to call it 'fart and squeak.' And he turned down any number of minimalist pieces calling them arbitrary. What we both loved was melody - melody which lets beautiful voices soar."

Benson remembers "Jerry always had a song project or a commission in the works." Crafts tells of meeting Hadley in San Francisco and finding their views of contemporary music copacetic. "We agreed on what it should be and perhaps more importantly what it should NOT be," Crafts says. "Jerry had no use for the perpetually dissonant styles -- he used to call it 'fart and squeak.' And he turned down any number of minimalist pieces calling them arbitrary. What we both loved was melody - melody which lets beautiful voices soar."

Cheney says that Hadley taught him to sing "from a physical perspective. It's not about placement and all about the mechanism." Hadley also shared with Cheney his approach to interpretation. "He was freeform; he would start talking about a role and how to give the conductor what he wanted while still bringing your own thoughts to the table. He was amazing with text, and he would bust my chops to sing meaning, not just language."

Cheney says that Hadley taught him to sing "from a physical perspective. It's not about placement and all about the mechanism." Hadley also shared with Cheney his approach to interpretation. "He was freeform; he would start talking about a role and how to give the conductor what he wanted while still bringing your own thoughts to the table. He was amazing with text, and he would bust my chops to sing meaning, not just language."