|

|

by Carla Maria Verdino-Sullwold

|

|

"The three most important things for a composer are melody, melody, melody. All great works have in common memorable melody." At first glance this statement seems to be an obvious one for a musician to utter, but for New Mexico-based contemporary composer Daniel Steven Crafts, the defense of melody has been a life-long crusade -- a cause celebre that has pitted him passionately against many of the fashionable 20th century trends of atonality, minimalism, serialism, and formalism. In 1991 while working as a radio and print journalist, Crafts says he grew tired of presenting a new music series on his radio show. "No one called in; no one listened, and I finally had had enough!" And so, the composer threw down the gauntlet by publishing in the San Francisco Bay Guardian a manifesto entitled, Escape from the Dungeon of Dissonance. The essay produced shock waves throughout the musical establishment. "It made me an anathema to the new music community. I even got death threats," Crafts remembers. Speaking today more than twenty years later, Crafts concedes that "the pendulum [of musical taste] has swung back a little," and he acknowledges that his adamant stance and his own unabashedly tonal and melodic compositions have sometimes made his journey as a composer a difficult one. "To get my music performed has been a challenge because I fell between the cracks as a composer. The new music people didn't want me, and those committed to the standard repertoire preferred the old masters." Still, Daniel Steven Crafts has persevered and has prevailed. Born in Detroit, a city which, by his own admission, he left as soon as he came of age, Crafts took up residence first in the San Francisco Bay area and recently in the New Mexican desert. Crafts considers himself a largely self-taught composer. "I tried to play a number of instruments," he recalls, "and I learned the basics of several, which has helped me in writing orchestral music, but I never had the patience to practice."

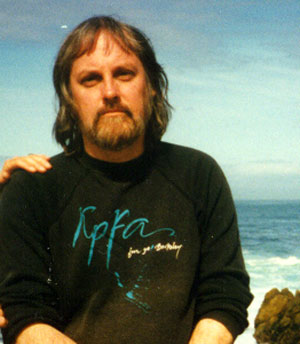

Crafts recounts how his path diverged from academe almost from the start. "I had been accepted into a graduate program at a university with a prestigious music program, and I went for a interview with the head of the Composition Department. I was pretty cocky in those days, and I remember telling him that I was not interested in spending any time with twelve-tone music. I said that I found it aesthetically repugnant and politically and philosophically reactionary. With a wave of his hand, he replied, 'Then, I guess we have nothing to teach you. Go write rock and roll!'" Crafts chuckles at the memory as he explains that after the encounter, he substituted intensive self-study. "I spent years pouring over scores from the old masters and trying to teach myself everything I could about all kinds of music from Gregorian chant to the 20th century works I considered worthwhile. And as he learned, he experimented with his own compositions. He wrote and wrote -- an oeuvre which to date is comprised of a dozen operas, nine symphonies, six concerti, five large orchestral works, and a proliferation of songs and shorter pieces. Yet, despite his passionate commitment and his output, choosing the métier of composer in the late 20th and early 21th centuries has often proved to be an uphill struggle. When asked how one makes a living as a contemporary composer, Crafts wryly responds, "I'm still trying to figure that one out. I get a few commissions, but I also have to be resourceful and support myself in any way I can." Over the years, those "day jobs" have included working as a substitute teacher and as a journalist and radio host for KPFA, in which posts he interviewed the likes of Jess Thomas and Jerry Hadley. It was the meeting with the late tenor Hadley that proved to be a fortuitous one. "If you can imagine my living in a rat hole of a Berkeley apartment and coming home to a message from Jerry asking me to compose something for him! Talk about life-changing experiences!" Ironically, it was Crafts gift for melody that captured Hadley's imagination, and the ensuing project on which they collaborated, The Song and the Slogan, a song cycle set to Carl Sandburg texts, won an Emmy for its PBS televised performance in 2003. The cycle helped put Crafts' name on the radar for contemporary composers, and the performances helped rejuvenate Jerry Hadley's late career. Crafts went on to compose more songs for Hadley, as well as his full-length opera, La Llorona and another song cycle, To a Distant Mesa. The ambitious scope of those recent works contrasts intriguingly with the beginnings of Daniel Steven Crafts' compositional career. His earliest experiments as a composer in 1970-1980 were in a genre known as "Found Sound" -- the combining of recorded tape and other existing sounds to create a collage-like composition. "I started with tape compositions when I was sixteen, and I have moved a long way from there over the years." But even in these experimental early pieces like Snake Oil Symphony and Soap Opera Suite, the composer differed from the mainstream moderns of the period. "I liked to combine found sound, speech, sound effects, and music in the traditional sense into a piece that had content, that coalesced into something more than just abstract sound." Snake Oil Symphony, for example, which subsequently attained the status of a cult work is, Crafts says, " a metaphor for capitalism; we all have something to sell." While the composer has long since abandoned this electronic experimentation, Crafts is amused at the place Snake Oil Symphony seems to hold in the annals of 20th century music. "To this day I get orders from people on every continent (except Antarctica) for the recording. Universities use it in their music history curriculum, and alternative radio stations still program it."

The impetus to experiment has not left Crafts thirty-five years later. His most recent new genre is a form of musical theatre he has dubbed "Gonzo Opera." "It began when Shannon Wheeler sent me this funny scenario for a one-act opera called Too Much Coffee Man, which I set to music. Shannon then went out and arranged for its performance at the Portland (OR) Center of the Performing Arts, and it was a hit! So, I have written six more with other librettists, and then decided the form needed a new name, so I came up with 'Gonzo Opera.' It has an Italian connection and, of course, references Hunter S.Thompson." The appellation seems to fit perfectly the wild and crazy style of operatic comedy for small casts and ensembles which Crafts is writing. "My goal in composing these Gonzo Operas," Crafts explains, "is to combine the two things I love most: beautiful voices and comic satire. I knew I could never do this in a traditional opera setting, but by using a small instrumental combo, the work becomes portable, and that opens a whole new realm for composing pieces that examine the relationship between music and comedy in the 21st century." While, with this new invention, Crafts' creative arc may seem to have come full circle in recent years, in fact, his compositorial opus is remarkable for its breadth and versatility. Crafts modestly attributes his prolific bent to necessity. " I would finish a work and make an effort to get it performed and often come up with a blank. So I'd put that piece away and start with something else," he laughs. Still, along the way there have been some notable commissions such as Entrance to the City of Proud Fancy for Chicago's Northwest Symphony and Fanfare Overture for the New Mexico Symphony. In the latter Crafts' gift for exuberant melody is heard in counterpoint to the ominous strains of the percussion until the two voices blend triumphantly. Or there is the haunting My Mistress Suite, commissioned by conductor Kent Nagano for the Berkeley Symphony, in which Crafts weaves the melodies of medieval Flemish composer Johannes Ockeghem into a four-movement orchestral piece that moves from the lively dance rhythms of the chanson through the slow and stately, even elegiac meditations of the winds and strings and culminates in a complex tapestry of strings and brass. "I'm a great fan of the cello and the French horn," Crafts confides, but I am also now becoming fascinated by the wonderful properties of the bassoon, the oboe, and the clarinet," says Crafts, whose first movement of his Bassoon Concerto was recently recorded by the Kiev Philharmonic. "But the voice is my favorite instrument; beautiful voices transport me to another world." And arguably, it is with his vocal works that Crafts has achieved some of his finest and best-known compositions. "I am always looking for texts to set," the composer says, "but they have to be texts out of which I can make melody. This usually means fairly regular rhythms, and this is not common in modern poetry. Just putting notes to words is not making music." Crafts has employed texts by the novelist Rudolfo Anaya (From A Distant Mesa) and poet Adam Cornford (The Pied Piper), as well as mining the entire spectrum of classical literature for libretti and song texts. Of the numerous theatre

pieces, choral works, and song cycles composed to texts by Shakespeare,

Shelley, Coleridge, Rossetti, Arnold, and Poe -- to name but a few --

perhaps Crafts' most ambitious and memorable is his treatment of William

Blake's Songs of Innocence and Experience. Written for full

orchestra and four soloists, to date this magnificent work has only been

performed and recorded in its piano reduction. While one longs to

hear all the orchestral complexities, the existing recording does

reveal Crafts' affinity for the mystical Romantic poet-genius.

"Blake did not flinch from the worst that human beings are capable of,

but throughout the poems, there is a glow," Crafts says. And it is

that radiance which the composer has tried to evoke in his music.

Much like the illuminations which Blake drew to accompany his poems,

Crafts' song settings shimmer with mystery, melancholy, and

transcendence, captured no where more poignantly than in the plaintive

question posed by the tenor at the close of The Tyger: Did he who made the Lamb make thee? To this meltingly lyrical query Crafts frames Blake's unspoken answer in the somber resonance of dark chords.

The composer's operas include Diary of a Madman and Bartleby the Scrivener to libretti by the director and radio personality, Erik Bauersfeld, and the recent opera La Llorona to a libretto by Chicano writer Rudolfo Anaya. La Llorona combines the Southwest legend of the Weeping Woman with the story of Cortes and his conquest of the Incas. Betrayed by Cortes, who seduces her but then marries a Spanish princess, Malinche, like Medea, drowns her son and cursed must wander the world in tears. The three-act opera, originally written for Jerry Hadley, was eventually performed in 2008 by Brian Cheney as Cortes, Deborah Benedict as Malinche, and Alissa Deeter as the Spanish princess in a semi-staged version at the National Hispanic Cultural Center in New Mexico and in concert excerpts in San Francisco. "If I have a voice in mind," -- as Crafts did with Jerry Hadley -- "I hear it in my head, and it is easy to create a work that shows all the capabilities of this wonderful instrument." This is precisely what Crafts did in his two majestic song cycles of the past decade -- The Song and the Slogan and From A Distant Mesa -- written for Hadley and, like La Llorona, posthumously performed by the tenor's protégé, Brian Cheney (qv Jerry Hadley). Using Carl Sandburg poems which Hadley had selected for The Song and the Slogan, Crafts created an exquisite cycle of songs which premiered in 2000 in its chamber version with flute, oboe, French horn, cello, piano, harmonica, banjo, and, or course, tenor. Its performance became a reality through the championing of Barbara Hedlund under the auspices of the University of Illinois Urbana Champaign and the public television which recorded the cycle on location. The broadcast performance, which features not only Hadley, but also Hedlund on cello and Eric Dahlheim (one of Hadley's early mentors) on piano, won the 2003 Emmy for music. Of the piece Crafts says, "I had always admired Sandburg as a poet and a political figure. In many ways he was a forerunner of Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and Bob Dylan, but his verse posed some challenges because the poems avoided regular meter. But the ones Jerry picked worked well musically after all." Crafts affirms that he drew on American folk music -- hence the harmonica and banjo -- for inspiration in composing the piece, and he sought to evoke the spirit of the prairie -- "of those good people living their loves in harmony with the land." Translating the landscape into sound is something that attracted Crafts to his second work, commissioned by Hadley on texts by Rudolfo Anaya, Adam Cornford, and V.B. Price. To a Distant Mesa is a melodic meditation on the magic and mystery of the Southwest desert. The forty-five-minute orchestral setting is in three parts. The first, inspired by the Hopi-Navajo legend of the Spider Woman to poems by Adam Cornford has, Crafts feels "a very mysterious time out of time, time before time quality." The second movement is in Spanish: Rudolfo Anaya's paean to the Rio Grande in which the composer says he hopes "to have his music conjure the same sense of power and movement of this beautiful river," and the third by V.B. Price entitled Being the Waters sings of "the significance of water to the life rhythms of the desert."

Once again, after Hadley's passing it was Cheney who premiered the cycle in January 2013 with the New Mexico Philharmonic. The young tenor praised the work in a pre-concert interview by saying, "It's one huge, beautiful melody." Crafts, after the work's long journey to performance, was gratified to have it performed not only by Hadley's protégé, but also in New Mexico, where "with its wonderful sense of the land, it rightfully belonged." The circuitous odyssey of Crafts' compositions like The Song and the Slogan, From A Distant Mesa, La Llorona, and Songs of Innocence and Experience are, alas, not anomalies in the labyrinthine world of the contemporary classical music business. Asked what the greatest practical challenge facing him and his fellow modern composers, Crafts answers flatly: "getting performed." It is something of a conundrum, the composer explains. "You need to know someone to get a commission. I have never been part of the New York scene, and that makes all the difference. You are considered a 'local composer' if you haven't been performed in New York and some people think, 'Why should I pay attention?'" He cites the La Llorona subject matter, which, he says, "should have been an ideal fit for the Santa Fe Opera." Crafts also understands that with the current funding constraints orchestras and the musical establishment must program their seasons with caution. But, he puzzles aloud, "It's a weird scene in contemporary music. In the theatre a company can program classic plays together with new works, but in music there seems to be this hesitancy." Pressed as to why, he offers one possibility: "all those years of composers' writing dissonant pieces has turned audiences off. With the high price of tickets, they are reluctant to come to hear new works." This perceived state of affairs is something Daniel Steven Crafts seems to have accepted with exceptional good grace. Rather than dwell on the difficulties, Crafts has chosen to persevere. "I have this huge backlog of things nobody has ever seen, but once I finish a piece and make an effort to get it out there, I try to move on. I believe I have to spend my time fruitfully writing." So, he lets his music speak for him. And the music he writes adheres firmly to the aesthetic principles that have sustained him throughout his artistic life. "In great art the context should be complex, but the means of expression as simple as it can be," he wrote succinctly in 1991. "Music is a language, and to have meaning, it must be a social language -- one that can be universally understood," he adds. "Without a common vernacular, music ceases to have reason for being." And how, I ask, has Daniel Steven Crafts in his forty plus years of composing classical music contributed to that credo? He replies: "By emphasizing that MUSIC IS MELODY -- that it should be beautiful, enjoyable, and not abstruse." And then he adds with disarming simplicity: "All I have done is to persist, and if I have been at all successful, then I am happy." Carla Maria Verdino-Sullwold's reviews, interviews, and features on theatre, opera, classical music, and the visual arts have appeared in numerous international publications. She is also a Senior Writer for Scene4. Read her Blog. ©2014 Carla Maria Verdino-Sullwold

|